The Rise and Dynamics of Counter-Narratives During the Covid-19 Pandemic

How failures in maintaining institutional legitimacy opened the door for mis/dis-information

From the inception of the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been major questions concerning the propagation of accurate information and approaches to minimizing the spread of mis/dis-information.

Over the period since, many heterodox narratives have developed in opposition to the primary narrative being put forward by public health authorities, despite efforts to combat them. In mid-February, 2020, the WHO (World Health Organization) announced that the novel SARS-COV-2 outbreak was accompanied by an “infodemic” of misinformation.

This raises the question, what are the factors at play that give rise to these counter-narratives, how has the media and public health authority failed in communicating (in turn allowing said narratives to propagate), and what can be done moving forward to address these insufficiencies?

Dynamics of Misinformation/Disinformation — Shared Features and Psychology:

One major question when considering the nature of heterodox narratives is what commonalities are shared between the conditions they tend to thrive in and the people who believe them.

In order to answer this question, we must establish how power and authority over the public psyche are negotiated within society in the first place. According to Spanish sociologist Manuel Castells, the battle for the human mind is fought largely through the processes of communication, it is through these spaces that power and influence is decided.

For him, power represents the structural capacity for a social actor to impose their will over other social actors while counter-power represents the capacity of a social actor to resist and challenge power relations that are institutionalized.

In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, this struggle between power and counter-power takes the form of mainstream journalistic/public health institutions fighting for control of the narrative believed among the public in opposition to a cavalcade of counter-narratives, many of which actively seek to undermine the perceived legitimacy of aforementioned mainstream institutions.

The spread of false and misleading information is not a new phenomenon, in fact, if we look to the 20th century, we can find multiple examples of this very problem, such as with the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, headed by Joseph Goebbels.

There is, however, novelty in the manner in which mis/disinformation is propagated and consumed, with the rise of online information ecosystems. This is especially of note for the dynamics of information communication over the pandemic period, as during that period there was a significant spike in internet usage of around 50%-70%, most likely in large part driven by pandemic restrictions leaving people more reliant on the internet as a source of socialization and entertainment.

We can see from works like Julian Dibbell’s “A Rape in Cyber Space” how as online communities form, the line between the real and digital can quickly become blurred, leaving people more susceptible to being influenced in those digital spaces.

Castells described the shift from other forms of media communication like T.V. to the internet as a shift from “one-way message” or “one to many” modes of communication towards a “many to many” or “synchronous and asynchronous” mode of communication.

This shift brings with it considerations of a different nature from traditional mass media. Digital technology and social media facilitate high-speed information sharing as well as cross platform cascade, making the ability to control the movement of information in these spaces difficult.

This rapid cascading effect of information combined with the fact that false narratives tend to outperform true ones in terms of engagement and popularity in these online spaces reveals a worrying vulnerability in our information infrastructure. One that was greatly exploited during the rise of the many heterodox narratives that came into being during the pandemic.

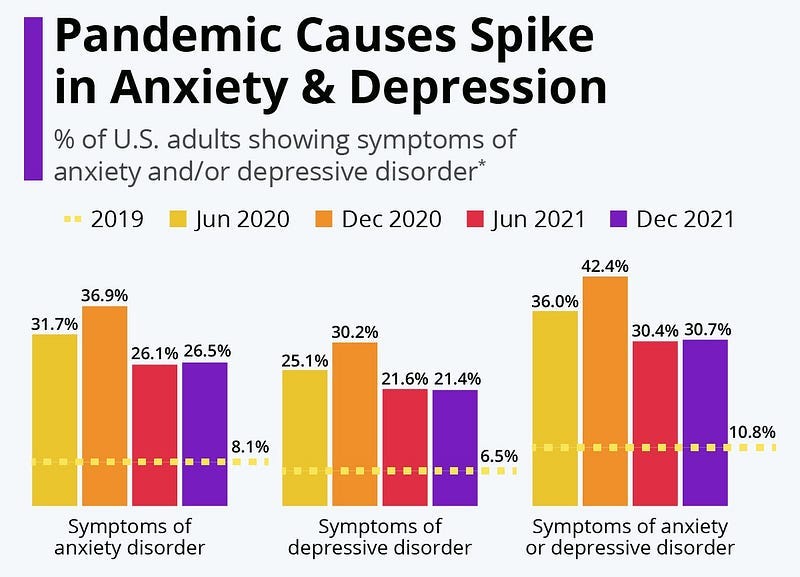

During times of great social crisis, misinformation, conspiracy theories, and alternative truths tend to thrive. This is because these periods tend to be correlated with low trust in institutions and high levels of fear amongst the public, allowing counter-narratives to seep in to fill any gaps left by the mainstream narrative and in many cases undermine it.

This plays into Castells’ conception of counter-power having more leverage during periods in which power is undergoing a crisis of legitimacy. This was definitely the case with Covid-19, which could be considered as one of “the first deeply mediatized global pandemics”.

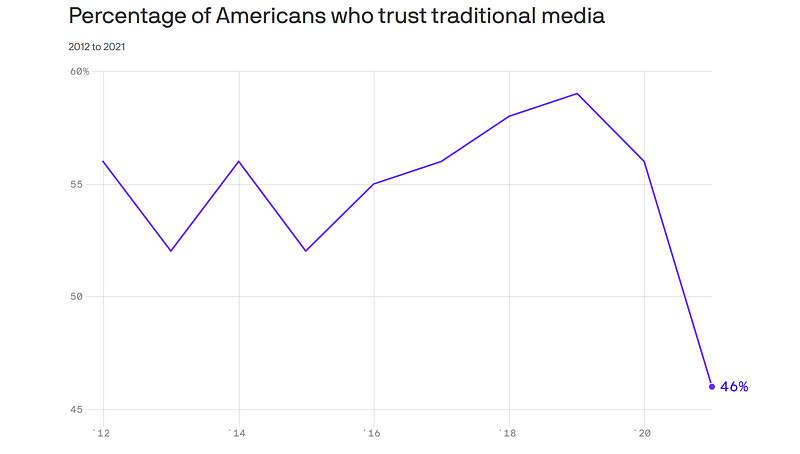

While mere exposure to false information can mislead people, research shows that trust in media also plays a significant role in how susceptible people are to these kinds of narratives, with distrust in traditional media sources having the confounding effect of both driving people towards alternative sources of information, like the internet, where they are more likely to run into selective exposure to mis/disinformation, as well as leaving those same people more open to accepting that false information as truth.

In societies where trust in professional media is higher, such as in Switzerland, resilience to conspiracy theories and misinformation has been found to be higher than in countries where trust in professional media is lower, such as the United States.

Times of global health emergency are generally associated with increases in psychological distress and uncertainty. In order to reduce this level of psychological distress, people employ sense-making functions to craft narratives that fill in the gaps of uncertainty in their current situation, with conspiracy beliefs being considered a “feature of the mind” meant to help regain a sense of certainty and control during these times.

This combines with a natural information seeking cognitive orientation to form a feedback loop that causes people to expose themselves to more stress inducing information, leading them to further craft narratives in order to regain a sense of control.

It doesn’t help that the majority of misinformation, about 59% according to a Reuters’ media fact-sheet, is reconfigurations of existing true information as opposed to full on fabrications, making it more difficult to disentangle truth from fiction.

A Crisis of Lost Institutional Faith:

As previously discussed, a major factor in the ability for mis/disinformation and counter-narratives to spread is the loss of faith and legitimacy in mainstream institutions, specifically our journalistic and public health ones. During the Covid-19 pandemic, faith in both traditional media and the government reached near record lows.

While part of this may be unavoidably embedded in the nature of attempting to communicate incomplete information to the public during periods of high scientific uncertainty, there are also points of preventable failure that both our media and public health bodies dropped the ball on. By analyzing these failure points, we can identify how to better avoid loss in legitimacy in order to more successfully combat inaccurate counter-narratives moving forward.

In order to elucidate this point, I have chosen a few examples of failures by the mainstream media and public health institutions that have likely contributed to the degradation of public faith in them. The first one I have chosen to discuss surrounds the failure to adequately convey uncertainty surrounding the origins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus during earlier points of the pandemic.

Near the beginning of the pandemic, there was a major focus on trying to establish where SARS-CoV-2 originated. The 2 major competing theories were the Zoonotic Spillover Origin Theory, where it was posited the virus had naturally jumped from some unknown animal vector to humans through contact within the Wuhan wet markets, and the Lab Leak Theory, the idea the virus originally leaked from the WIV (Wuhan Institute of Virology).

There were also many sub-theories, all varying widely in plausibility. The Lab Leak Theory specifically spun off a ton of unsubstantiated theories that in some cases relied on mistranslated information which skewed conclusions.

This entanglement with conspiracy led to a more dismissive engagement with the Lab Leak Theory by mainstream media, but while there were plenty of conspiracy theories around a lab leak origin for SARS-CoV-2, the idea that there was the possibility that the virus had leaked from a lab shouldn’t have been treated as conspiracy.

In their attempt to push back against more extreme unsubstantiated versions of the claim, many publications ended up casting too wide a net, causing them to cast undue dismissal onto reasonable positions.

Examples of mainstream media sources jumping the gun on dismissing the possibility of the Lab Leak Theory include publications from across the media landscape such as Vox and The Washington Post. The main problem here is that in many of these cases there is a conflation of multiple forms of the Lab Leak Theory, with much of mainstream media only engaging with the most extreme version, the idea that the Chinese government had engineered the virus as some sort of bio-weapon and intentionally released it.

This conflation led to more reasonable versions of the theory getting swept away, so when in late May, 2021 a U.S. intelligence report identified that three researchers at the WIV had sought treatment at a hospital after falling ill with Covid-like symptoms in November 2019, leading to further probes into a possible lab leak origin for SARS-CoV-2, it undermined previous reporting by media sources, backfiring into ammunition that more extreme actors used to further diminish public perception of institutional legitimacy.

There was a similar effect when a letter signed by 27 prominent scientists came out in the Lancet, made in support of scientists and medical professionals in China fighting the outbreak of Covid-19, condemning theories suggesting that the virus did not have a natural origin. When it came to light that the scientific community wasn’t as unified on a firm idea of a natural origin as the letter had made it seem, it ended up negatively effecting trust in our public health institutions.

In both cases, keeping a more neutral stance reflective of the scientific uncertainty at the time would have been more likely to avoid the losses in public perceptions of institutional legitimacy we see now.

Another example of this is seen in the initial media coverage of the anti-parasitic drug Ivermectin, a drug which became an obsession among vaccine skeptics as an alternative treatment for Covid-19. At the time there was, and continues to be, very limited to negative evidence of the drugs clinical effectiveness in treating the disease.

On September 1st, 2021, KFOR, an Oklahoma news channel, reported that rural hospitals throughout the state were in danger of being overwhelmed due to an uptick in poisonings from people overdosing on Ivermectin. The story went viral, being covered by multiple mainstream news sources.

It seemed to be a coming to fruition of everything mainstream liberal media organizations had been warning might happen in criticisms levied against right-wingers and anti-vaxxers promoting use of the drug. The only problem was that the entire story was false.

There was no evidence that Ivermectin overdoses where the cause of any major strain on Oklahoma hospitals, and the doctor quoted in relation to that claim never actually drew the connection between Ivermectin overdoses and hospital strain. That framing seems to have originated from KFOR itself.

In their affirmation of their own biases, the media failed to do the adequate due diligence, parroting reports without scrutiny, and ultimately diminishing public faith. This, tied with the flood of characterizations of Ivermectin in the media as “horse dewormer” despite it clearly having applications in humans, only served to provide ammo for pro-Ivermectin, anti-vaxx groups to use as a way to undermine the official narrative and push their own.

The final example I will touch on with regard to failures by our institutions to maintain public legitimacy is the CDC mask fiasco of early 2020, when on April 3rd, the CDC flipped its guidance to a near universal recommendation for mask wearing after initially advising against it.

This flip-flopping on guidance, though it seemed to have been done as a “noble lie” meant to avoid panic buying of masks that could have led to a shortage of supply among front line health workers who needed them the most, served to fuel suspicions that public health guidelines weren’t being adopted out of any “scientific rationale”, again providing ammunition for counter-narratives to undermine the mainstream one.

Over time each of these individual slip-ups coalesce into a larger feeling among the public that all the institutions have no credibility, and without faith in those institutions as a guiding beacon, people just end up gravitating towards whatever sources of information reaffirm their preexisting biases, regardless of whether those sources maintain a high standard of quality.

Addressing Future Approaches — How Can We Learn from Our Past Mistakes:

With all this in mind, it is important that we take the lessons we have learned throughout the Covid-19 pandemic and utilize them to craft a framework for addressing insufficiencies in our current approach, as to not fall victim to the same issues in the future.

It is clear that any path forward will require a concerted effort to rebuild institutional trust, inoculate people to bad information so that they are less susceptible to dis/misinformation exposure, and increase the public’s tolerance to uncertainty.

In order to do this, I have put together a collection of preliminary recommendations, sourced from studies exploring this very topic, covering ways to better communicate and combat mis/disinformation. Ideally these and other tactics can serve as a foundation for future development in the direction of better approaches to addressing these issues.

As I’ve already discussed above, the establishment and maintenance of institutional legitimacy is paramount when it comes to the effective propagation of factual information over mis/disinformation. With our national media, political, and health institutions facing significant reductions in public faith, we must look to sources of information that people still have higher degrees of respect for.

Local health departments and local media organizations tend to enjoy higher levels of trust within the communities they stem from than their national counterparts. By supporting and partnering with these and other local organization, our broader institutions can leverage that trust into building better legitimacy as a whole, however, this is a process that must be approached with care, as there exists the possibility of a backfire if significant enough mistakes are made which could threaten the levels of trust said local organization currently enjoy.

Moderation of online content is a nuanced debate, approaches like censorship on social media can prevent the spread of viral misinformation to the general public if done early enough, however, too much censorship runs the risk of driving further polarization and undermining democratic freedoms.

It also runs the risk of incurring the Streisand effect, bringing more attention to the misinformation than it would have otherwise seen. Fact checkers can be effective in combating false information, however, they require more investment into independent fact checking organizations in order to keep up with the massive inflows of information, and have limited access to misinformation spreading via private channels.

When prevention of exposure to misinformation is impossible, it is important to build media and health literacy skills in order to diminish the public’s susceptibility to mis/disinformation, taking on a pre-bunking approach as opposed to a debunking approach. By doing this we can increase the public’s tolerance for uncertainty and reduce levels of stress incurred.

Transparency is important for building trust, however, without developing the necessary public literacy, it can become harmful. This can be seen with the rise of pre-print culture where, though useful for increasing the speed by which researchers can gain new knowledge, poor quality pre-prints can be used as fodder for conspiracy theories and mis/disinformation campaigns, taking advantage of lack of public knowledge in regard to research standards.

An example of this is the notorious Ivermectin pre-print (Elgazzar et al), which was the go-to study for Ivermectin supporters before it was discovered that the paper had major flaws and was potentially fraudulent, eventually being withdrawn from the pre-print platform it was hosted on.

All of these are merely first steps in a far more comprehensive process that must be undergone in order to address the insufficiencies of our current approach to combating false counter-narratives. Times of great social crisis, like a pandemic, tend to leave us at our most vulnerable.

It is at these points, that we must rely the most on our institutions to function properly and get us through. In order to do that they must maintain a certain level of public legitimacy. Without that legitimacy, other actors will appear to fill in the gaps, and in an era of a constantly shifting media landscape, our modes of communication are as unpredictable and dynamic as they have ever been.

It’s up to us to craft a system capable of maintaining strong information standards despite the obstacles and ever-changing landscape.